|

By Pat lefemine |

| |

You've earned your trophy. You scouted all summer and fall. You hung your stand and waited for the perfect wind. And when things fell together perfectly you made a great shot and collected your best animal ever. He hangs on your wall along with a dozen other priceless trophies to treasure forever - right? Well, maybe not.

You pass by your prized mount hundreds of times. What you don't realize is that it is under attack by something that moves so slowly, quietly and deliberately that most people never notice anything wrong. Then one day you move your mount and ten square inches of fur just falls out like it's been buzzed with a number 0 hair clipper. You are dumbfounded and immediately check your other mounts - only to find the exact same thing is occurring across your entire collection. Sound far fetched? I thought so, until it happened to me. Luckily, I was aware of the warning signs. I knew exactly what was happening, and who could fix it. After you read this feature, you will too.

The Crawling Culprits

Remember when your mom used to store her good wool clothing in those old cedar chests with mothballs sprinkled liberally across the bottom? This was to keep out the common clothes moth (along with case-bearing moth) from using her sweaters as a buffet. While the cedar lined chests and mothballs may be history, the moths are not. And they have developed a taste for something new - your mounts. And it's not just the moths, there are also a host of beetles that have a voracious appetite for the keratin protein that encircles the base of the hair on your heads. Now, let me clarify an important fact; the flying moths and the hard shell beetles are not your problem.

All the damage, to either your sweaters or your stone sheep, are done by the larvae stage of these insects. The beetles and moths lay their eggs on your mounts and they grow by feeding through the hair until they emerge as an adult which utlimately lay their eggs too, thus starting the cycle all over again. Only this time the damage is increased exponentially. If you miss the warning signs and allow several generations of these bugs to propogate, it's conceivable your entire collection could be destroyed in a single year. (See the bug identification guide below for more details on these pests).

Why the new threat? Thank the EPA

If you've been hunting a long time like I have you are probably wondering why people with trophy collections for years never had this problem. There is an explanation: Prior to 1993 arsenic was a key ingredient in the tanning process. Commercial tanneries - the ones your taxidermist likely used - included arsenic to keep furs and capes from becoming a target of insects. When the Environmental Protection Agency placed Arsenic on the list of the top 200 known carcinogens, tanneries were forced to remove it from the process. From what I understand, tanneries were allowed to deplete their stockpiles so the exact date that arsenic treatments ceased may vary. But it's safe to say that now US based mounts are no longer protected against bugs.

Early Detection is the Key

Watch our Inspection video where Bugs were found (40mb)

Ok. So now that I've scared the crap out of you and you are all racing to your mounts for an inspection let me explain what you need to look for:

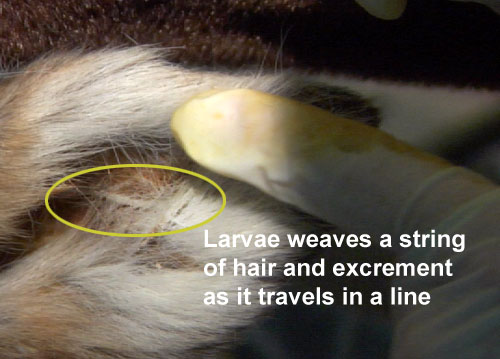

- Lines or tracks in the hair - the larvae often will travel in a straight line and produce tracks that are visible on the pelt. Likely areas of attack include the base of the horns and ears.

- Sawdust on, or under the mounts - if you routinely see what looks like sawdust on or under your mounts you have a problem.

- Rice-Krispie looking shells on or under your mounts - this is the empty larvae casings. This is what I found on the feet of my grizzly bear and prompted me to perform an in depth inspection of my entire collection.

- Hair slipping out in clumps - the larvae move methodically along the top of the skin where the hair connects and they eat the protein that surrounds the hair. Like a beaver chewing around a tree. The hair will often cling together until enough of it is detached that gravity is greater and it can fall off in clumps. Pulling gently on the hair will confirm this is happening but DO NOT PULL IT OUT! Believe it or not it can be repaired by being glued back to the skin.

- Small Holes in hollow horns or bird legs - Horns (not antlers) are breeding grounds for larvae. Sheep horns are a real problem, same with the horns of African game. I had no less than 200 small 1/32" holes on my Impala horns. But the most susceptible critter is a turkey mount. In fact, my infestation was tracked back to my big gobbler from South Dakota. The freeze dried heads and legs are magnets for the bugs. They breed like crazy in turkeys. I removed my turkey from my collection and will never have another full mounted bird in my collection.

|

So now your infected - what to do?

You've followed our inspection tips above and you have confirmed you have a problem. What do you do? This is difficult to answer. When I realized my mounts were being attacked I hit the internet first to see if there were home remedies or techniques that would work. Some of these included placing your mounts in a deep freeze overnight, using bug bombs in your home, spraying chemical insecticides on your collection, and calling in an exterminator. The problem with all of these solutions were that they either were temporary (Freezing), ineffective (bug bombing) or dangerous to your mounts (sprays and using exterminators who's chemicals may affect color or cartilage like eyes and noses).

Update - 2012. Many of the photos and text from this article has since been removed. We used Miller Trophy Room Preservation at the time this article was composed but that company that is no longer in business and is currently under investigation by the Department of Justice. At this time, we have no recommendation for treating your mounts. If that changes we will reflect those recommendations within this article.

Bug Identification Guide |

| COMMON CLOTHES MOTH |

|

First of

all, the adult stage (the moth) does no damage to

fabrics or any other materials. In fact, during

it's adult stage, it eats or consumes no food, living on

what it consumes during the larval stage. It is

this larval stage that this insect causes any damage by

feeding on natural materials, wrapping itself in an open

and chaotic web-mat of silk. Larvae are not normally visible or obvious in their day to day

activities. The silk is produced by a gland just under the

head from a special spinneret. Larvae may reach a size of

almost a half inch and incorporate their rather large fecal pellets

into their web-like mass. The fecal pellets are often mistaken

for "eggs."

Adult females lay their eggs, all within a couple

of days, fertilized or not, on substances that will support the

larval stages. Unfertilized eggs, of course, do not hatch, but

fertilized eggs will hatch, in a matter of days, depending on the

temperature, and the larva will then crawl away and hide.

Larvae molt some four times before they construct a cocoon to

pupate. Cast-off pupal skins can often be seen protruding from

cocoons.

The Common Clothes moth, in the larval stage, is the

most important pest of Man's natural materials, far more than the

Case-bearing moth, which looks quite like the Clothes moth. And

yes, these pests can go from life cycle to life cycle, right in your

house, in your closet or attic.

To minimize the chance of

either of these pests, have your natural material (wool, linens,

etc.) dry cleaned after each use. DON'T put them away "dirty."

Clothes moths prefer to dine on materials with traces of body

oils, perspiration and urine, so if your items are absolutely clean,

you'll worry less. Our bodies constantly exude minute amounts

of these attractive chemical tags, and just ONE wearing is enough to

attract these pests. The larvae can leave

large holes in natural materials. |

| CASE-BEARING MOTH |

|

So named because the larvae carry their pupal cases about as they feed and travel, case-bearing moths are much less likely to be found in your home than the Common Clothes moth.

Look for the faint, dark smudges on the wings of the adult. Â The wings have a very slight, darker, dusky appearance, compared with the clothes moth, giving it a slightly dull appearance. Â The eggs are visible only under a low-power microscope. Â The larva of the Case-Bearing moth is much more easily identified because of their cases, open on one end, and dragged about, wherever they go. Â The larvae only expose the first few segments, staying within their case for protection.

The larvae never leave their cases, and when ready to pupate, will seal off both ends of the case, and when the adult finally emerges, they cut through the end of the thin silken case. Â The Case-bearing moth is usually found around carpets and heavy woolen draperies. Â Case-bearing clothes moths are not that economically important, certainly not as much as the common clothes moth. |

| FUR BEETLE |

|

The Fur beetle and the Black

Carpet beetle are usually described together, the only difference is

the Black carpet beetle has white or yellow hairs on the wing

covers. The larvae look hairy, with color bands, have a tuft of

hairs at their posterior. You can usually see the cast-off skins,

which have the same banded appearance. Larvae avoid light, and when

disturbed, will "play possum" and remain immobile for a short time before

resuming activity.

The larva will pupate, invisibly, at the last

molt, right inside the last larval skin. New adults will even remain

inside the last skin for up to three weeks, before flying off to feed on

the pollen and nectar of flowers. The adult stage is attracted to light.

The adults are essentially outdoor

insects, mate and feed on flowers. After mating, the adult females

seek out places to lay a total of almost a hundred eggs in any material

that will support the larvae, such as bird nests, rabbit warrens and

animal burrows. With indoor situations, items such as woolens, rugs

and curtains are at risk of infestation. |

| VARIED CARPET BEETLE |

|

Adult carpet

beetles are about an eighth of an inch long, and round in

appearance. The backs of the insects have much the same

color scheme as the larvae. The larvae have small,

hairy, soft bodies about a quarter inch long, depending on the

instar. The larvae feed on a wide variety of foods,

including carpets, furs, woolens, skins, stuffed animals, leather, feathers, silk and many plant

products. The adults feed on nothing except pollen and nectar

from flowers outside.

In spring and early summer, the adult

will lay up to a hundred eggs, usually cemented to the product, or

on furs, woolens or any dried natural or animal material. The

eggs hatch in about three weeks.

The larval stage can

withstand a long period of no food, and can molt as many as 30

times. They also prefer clothes or fabrics soiled with

perspiration, body oils and urine. As with Black Carpet beetles, the

adults will pupate in the last larval skin and use the last skin to

hide in for as long as a month. |

| FURNITURE BEETLES |

|

Adult Furniture beetles are found all over the

world, are about an eighth of an inch long, with mottled

yellow, white and black scales. The underside is white.

They attack a wide variety of materials, including

clothes, furs, feathers, hair, wool, tortoise shell, silk,

dried and preserved animal skins and horns, and even dried

cheese, dried blood, and book bindings. They also attack leather,

cotton, linen, jute and even softwood, especially if it is soiled.

Adult females can lay 60 eggs, in places where larvae are

able to feed. The eggs will hatch in about two weeks, and the larvae

develop over the next 60 days. Larvae of Furniture beetles are about

half that size, about a sixteenth of an inch, and covered with bands of

stiff hairs giving them a bristle-like appearance. Like others of

this same type, they pupate in their last larval skin, and will emerge

from the last molt in less than two weeks. |

| LARDER BEETLES |

|

Larder Beetles are a

good 3/8ths of an inch long and have a distinctive band of

yellow-white across the upper third of their wing covers.

The banded area has several (usually three) dark spots,

symmetrically, on each wing cover. You can see, with the naked eye,

that it also has clubbed antennae. The underside of the body

is covered with very fine yellow hairs.

Larder Beetles

overwinter on the outside, enter homes and other buildings, usually

in the spring or summer. In addition to the things you

normally think they might infest, they also infest cured meats such

as ham, bacon, dried beef and fish, cheeses, animal skins, feathers,

animal horns, skins, and stuffed animals. They also are

attracted to dead animals, or accumulations of feces.

Adult females can lay about a hundred eggs during

their lifetime, and place their eggs on ready food material.

The eggs hatch in a short time, about a week or ten days, and

the larvae immediately bore into the food material. They molt

several times, five times for the male, six times for the female.

Just before pupating, they crawl away from infested materials

and will often burrow into soft wood.

Few people cure meats

in their homes anymore., so the problem is usually associated with

inside infestations of mice or other rodents. The beetles can

seek out and find these animal carcases and this is when the

homeowner can have a problem. The bad news is that you will

generally need the help of a professional exterminator to clear up

this problem. And it won't be easy. It will take an

extended program of insecticide applications to be sure this problem

is entirely eliminated. |

|